Illustrated by Gloria Kamen

Illustrated by Gloria Kamen

(Golden Press, 1965)

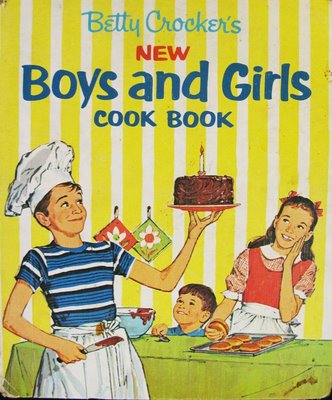

This is the first of a

week-long focus on an oft-overlooked nonfiction category, cookbooks for

children.

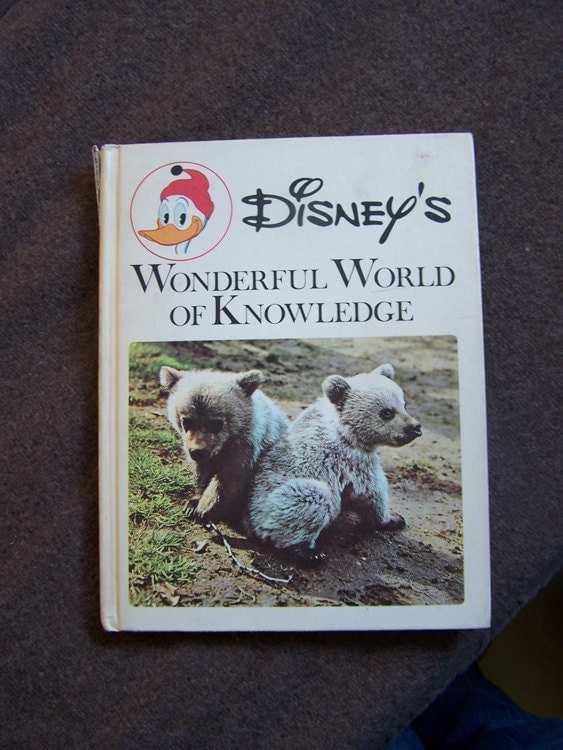

Aside from a couple of series (i.e., Thornton W. Burgess’s animal adventure books and Encyclopedia Brown mysteries), fiction wasn’t my thing when I was a kid. I wouldn’t say I was a big on nonfiction, but it was my preference by default. I frequently browsed through my Britannica Junior and Disney’s Wonderful World of Knowledge encyclopedia sets, I memorized facts on my hockey cards and I regularly consulted our two daily newspaper subscriptions, expanding my must-skim sections over time. And then there was one other pivotal book from my childhood, the spiral-bound Betty Crocker’s NEW Boys and Girls Cookbook. (Curiously, there is a space separating cook and book on the cover, but not on the title page. One would think a copy editor would have caught the inconsistency.)

This 1965 book follows the highly successful first

children’s cookbook, published in 1957.

One of the selling points for both books was that all the recipes had

been tested and regarded favorably by children who served as

“test-helpers”. Considering the time

period, it is remarkable that nine of the twenty-five children are boys. (After all, a few years later in junior high,

I would be gender-tracked, suffering through all-boys Woodworking while the

girls studied Home Ec.) Truer to the

times, all the children, based on their sketched portraits, are white with

typical English names like John, Joan, Ricky and Chris. As well, there is no cultural diversity in

the recipe list: no hummus, no Greek

salad, not even nachos. This is a book

that considers iceberg lettuce, hotdog wieners and fruit cocktail as staples.

The opening section, “What Every Cook Should Know”, contains

some must-read retro advice on staging a meal.

Under the heading “Setting the Table”, Betty states that family meals

should “[a]lways have a centerpiece—garden flowers, fruit, a little pot of ivy

from the window sill, or a figurine from the cupboard shelf.” (TO DO

this weekend: Scour through garage sale

heaps in search of figurines for my cupboard shelf. (PLAN B:

Bring in one of my beloved garden gnomes.)) Betty schools the reader on good manners,

with tidbits like “Wait to begin eating until Mother is seated and all the

family has been served” and “Wait until everyone has finished before you ask to

be excused from the table. When you are,

tell Mother ‘Thank you.’” In our home,

Betty would have been proud. With

nostalgic sadness, I read “Fun at Dinnertime” where Betty reminds us of the

lost art of communication over family dinners:

Dinner is the sociable meal of the day when

all the family gathers

around the table together, and everyone

tells what happened at

school, at work, and at play.

Betty adds, “Talk about happy subjects” and suggests a

conversation game called “Table Topics”.

Yes, let’s have families talk, but let’s not have it get too real.

As a boy, I salivated over the recipe for Polka-dotted

Macaroni and Cheese (the dots are sliced frankfurters liberally tossed on a

casserole dish of macaroni topped with “cheddar cheese soup”—is there such a

food item anymore?). Even then,

however, Meat Loaf à la Mode was an instant reject. No way a scoop of mashed potatoes suffices as

a fill-in for ice cream! And speaking of

turnoffs, the Italian Pizza, consisting of no spices and chopped onion as the

only veggie, risked steering a generation of youngsters away from the World’s

Greatest Food. The unappetizingly drab

photograph did not help. These were the

days before anyone dreamed up “food stylist” as an occupation. (Test-helper Mary Sarah shares the thinking

of the time in the beginning of the book, “Mother showed me how to cut parsley

and put it on top of soup. It looked

pretty there.”)

As a boy, I salivated over the recipe for Polka-dotted

Macaroni and Cheese (the dots are sliced frankfurters liberally tossed on a

casserole dish of macaroni topped with “cheddar cheese soup”—is there such a

food item anymore?). Even then,

however, Meat Loaf à la Mode was an instant reject. No way a scoop of mashed potatoes suffices as

a fill-in for ice cream! And speaking of

turnoffs, the Italian Pizza, consisting of no spices and chopped onion as the

only veggie, risked steering a generation of youngsters away from the World’s

Greatest Food. The unappetizingly drab

photograph did not help. These were the

days before anyone dreamed up “food stylist” as an occupation. (Test-helper Mary Sarah shares the thinking

of the time in the beginning of the book, “Mother showed me how to cut parsley

and put it on top of soup. It looked

pretty there.”)

I recall following the chocolate chip cookie recipe to

provide a surprise treat for my parents after they left me unsupervised for a

few hours as a nine year old. (There was

so little to fear back then. No AMBER

ALERTS, no internet reports of children abducted and entrapped in far off

Belgium. All hysteria was reserved for

testing whether laundry detergent could remove grass stains from little boys’

jeans.) Back to my cookie recipe,...the

ingredient “½ teaspoon soda” perplexed me.

Soda? Coke or Pepsi? In cookie dough?! I skipped that part and presented my parents

with baked goods guaranteed to knock out a few teeth. Lesson learned and emergency dental visit

miraculously averted.

I think I stared at the ice cream sundae pages the

most. If only my parents stocked our

freezer with something other than no-name Neapolitan. “Special Occasions” represented the second

most flipped to section. In addition to

festively decorated desserts for Halloween and Christmas, Betty provided handy

notes for a “Big Top” Party, complete with directions for place card balloons,

Popcorn Ball Clowns and a heavily candied Circus Parade Cake. I never tried to carry out a circus party—too

much work—but I imagined becoming everyone’s best friend if only my mom would

do it all.

I tried very few of the recipes, but gazing at and reading

about recipes that Betty believed I could handle proved infinitely more

entertaining than cracking open good-for-you Newbery Medal novels or

yet another Hardy Boys book my grandparents bought for my birthday. Betty

Crocker’s Boys and Girls Cookbook established a habit I still follow

today. Now a vegetarian, I regularly

purchase cookbooks and foodie magazines, thumbing through the pages, gazing at

the photos, visualizing the steps for particularly enticing recipes and then

relegating the reading material to a kitchen cupboard stuffed with unrealized

dreams. I can read about Mars and never

go there; same with oven adventures involving concoctions admittedly several

notches more enticing than Butter Sticks and Fruit Basket Upset. To this day, soup from a can seems so much

more sensible.

No comments:

Post a Comment