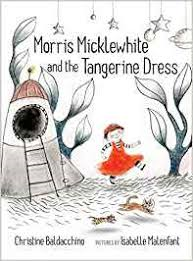

MORRIS

MICKLEWHITE AND THE TANGERINE DRESS

Written

and Illustrated by Christine Baldacchino

(Groundwood

Books, 2014)

10,000

DRESSES

Written

by Marcus Ewert

Illustrated

by Rex Ray

(Seven

Stories Press, 2008)

There

are books that make me wish I weren’t taking a leave of absence as

an elementary school principal. There are funny ones I long to read

to a group of eager kindergarteners or a room of resistant grade

sevens. There are captivating picture books with a-ha moments that

require an immediate second read to marvel over how the author

surprised the audience. And then there are the teachable books, the

ones with insights that build awareness and transform the reader with

new understandings. Morris Micklewhite and the Tangerine Dress and

10,000 Dresses are two

books I’d like to workshop, with staff, with students, with

parents. Fictional characters like Morris and Bailey can make the

lives of many real people a little easier.

First

up, Morris. He lives with mother Moira and his cat Moo. (Yes, the

alliteration is a little heavy at the get-go.) Morris is one of

those youngsters who likes many things. “Mondays are great,” we

are told, “because on Mondays, Morris goes to school.” So many of

the things he likes happen there. What Morris likes most is center

time, when he chooses to play dress-up. That’s when he gets to wear

the tangerine dress which “reminds him of tigers, the sun and his

mother’s hair.” He loves the swishes and crinkles he hears while

moving in the dress and the click, click, clicks from the shoes he

wears with it. But, “[s]ometimes the boys make fun of Morris.

Sometimes the girls do, too.” Soon Morris doesn’t want to go to

school.

On

the title page of 10,000 Dresses, we

see Bailey, smiling and wearing a simple white t-shirt and underwear.

The message: this is a boy.

But the story opens, perhaps

jarringly with, “Every night Bailey dreamed about dresses.”

There’s some awkward language about a stairway in a “red

Valentine castle” that had me frowning, but this is more of a

message book than a literary marvel. Bailey’s dreams involve

dresses of rainbow-flashing crystals and lilies, roses and

honeysuckles. Her dreams are instantly dashed by her parents. (Yes,

this 2008 book uses preferred pronouns of she and her for Bailey.)

“You’re a boy,” his mom says. “Boys don’t wear dresses!”

And

Bailey’s response is heartbreaking: “But...I don’t feel like a

boy.”

There

have always been Morrises and Baileys. But, in my day, they would

have to change. They would have to don and dream of dresses in

secret. Either that or the bullying would be relentless, stretching

from kindergarten to the great beyond. Morris would be mocked as

“Margaret.” “Melissa.” Or the much-maligned, all-purpose

sissy taunt: “Nancy.” But we’re in a time now when most would

recognize that it’s everyone else that needs to adjust. Morris is

just being Morris. Bailey can be whoever she wants. Why should anyone

have a problem with that?

Sadly,

they still do. As early as kindergarten, boys know to avoid pinks and

purples and to leave the dolls alone in the play centers...unless

they are being used to fire out of a make-believe cannon. Gender

roles are established, whether it’s due to nature, nurture or a

combination.

A

colleague of mine shared how she refused to buy toy guns or other

weaponry for her two boys and yet, even before they learned to wave,

they were using their thumb and index finger to form a quick-draw

gun. Bang! Bang! As I shopped for my cousin’s baby shower this

summer, I was dismayed that so much, from cards to gift bags to

stuffed animals, came in pink or blue. Baby Jack’s nursery is

painted green and adorned with gray whales, crabs and octopuses.

(Side note: turns out octopi is

an “improper

plural”.)

I am further reminded of a fascinating New York Times

article about trying to

reverse gender roles and also teach gender neutrality: “In Sweden’s Preschools, Boy Learn to Dance and Girls Learn to Yell”.

Some

may indeed be entrenched in their typical male or female gender

identification. The point is to open their eyes to the fact it’s

okay for others to express themselves differently and to open the

door for others to explore a more fluid or less typical gender

identity.

These

are important books to read and discuss with

children, perhaps more than once over a period of years. Despite

greater awareness of Morris and Bailey, gender-role and

gender-identity defying boys remain a minority. It is easy for peers

to find their behaviors and preferences queer,

in the “odd” sense of the word. If a child’s first

reaction—i.e., a boy wearing a dress is odd—is not elicited and

accepted, then the opportunity for transformational learning

decreases. A child may listen to the story and go away unchanged,

still reacting critically when he or she observes another child

acting outside of gender norms. Ridicule may go underground. Then

it’s a burden for the targeted child to have to muster

the courage to report or to have bear

in on his own.

Books like these seek to increase awareness and acceptance to reduce

burdens. They also provide

safe reference points for parents, teachers and children. “Remember

when we read that book about Morris and the orange dress...?”

Both

books are worth reading, perhaps a week or a month apart. (Pull out

the first book to read another time after the later reading of the

second book.) It helps kids to know that Morris Micklewhite

and the Tangerine Dress (or

10,000 Dresses) isn’t

some one-off book. There are positive traits about both characters

that should be elicited from the reading audience. The

boys-wearing-dresses images may be vivid takeaways but there is more

to admire about Morris and Bailey.